The Digital Commons EDIC was launched on 11 December 2025 in The Hague. I had previously praised the project for (hopefully) building a home for open social networks (in German). After the Bundestag’s budget committee had approved the federal budget for 2026, allocating a core budget of just €1.36 billion to the Ministry of Digital Affairs, I updated that post, noting that the German contribution to the EU Consortium for Digital Commons Infrastructure will be a meagre €240,000 in 2026. After the launch, it is time for another update.

At the celebration, the three initiators France, Germany and the Netherlands presented their national open office suites LaSuite, OpenDesk and MijnBureau. And of course, there were keynotes, including by Thibaut Kleiner, Director of Future Networks at DG CONNECT, representing the European Commission, by Art de Blaauw, the Technical Director of the Dutch government, and by Bert Hubert, entrepreneur, software developer and technical advisor at various government departments, representing his own tech smartness.

Since Hubert, in contrast to the others, was so nice to publish his presentation, he will be the lens through which I look at the launch.

I agree with nearly everything Hubert writes. His analysis of how bad things are, of Europe’s utter dependence on US and Chinese services. That governments need to become leaders in IT.

Requirements for a successful digital commons

I also agree with his six requirements for a successful digital commons, which are his central argument. I just don’t think they are sufficient. The first three of which are widely agreed on in the community: the commons needs to be Free Software and open standards, open implementations and gatekeepers with open governance.

The other three, Hubert writes “are often neglected and I hope that we can have a role here [as an EDIC]”: the commons product needs to also be provided as a service, with actual marketing and sales and it needs to be ‘good without excuses.’ On the latter point, I have to admit that I also tend to believe that what is good will prevail. But rationally, I agree with Hubert. Nobody will move away from a dominant platform because the alternative is European or Free Software. Particularly not, when they are told that it’s good but a bit tricky to install or the user interface is slightly clunky and so on.

What is a commons?

But then we come to “the tricky business of defining what a digital commons is.” Hubert starts out on a good track. If you have a digital commons, he argues, you have digital sovereignty, but not the other way round. With a European Amazon owned by Deutsche Telekom there is ‘sovereignty’ but as little commons as before.

I’m also totally with him in his critique of the “false digital commons”, i.e. services that are free to use and that people consider infrastructure for running their life, e.g. Google Docs, Youtube, Discord or ChatGPT.

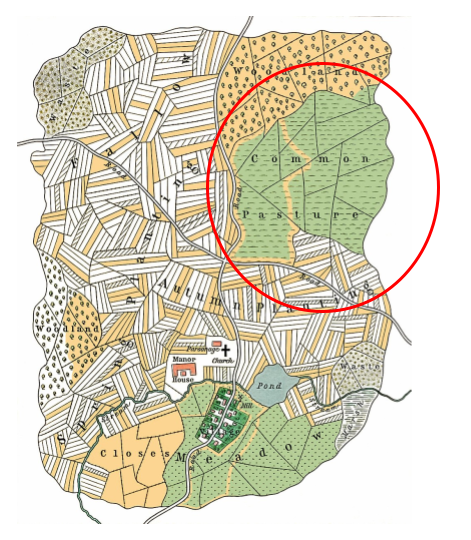

But then the account takes a wrong turn, precisely when asking: “What are these digital commons? Well, we heard this morning from the minister that it was this field where everyone could let their sheep graze and stuff.”

That you don’t have to ask permission doesn’t make it a commons

This single sentence evokes the idea of Garrett Hardin’s pseudo-commons – the one with the tragedy, introduced in a widely cited article in Science in December 1968 (The Tragedy of the Commons). And he continues: “I think they also had fights over that and who could put on their sheep there first. So it’s not that easy.” Here we see Elinor Ostrom appearing at the horizon: The idea that the commons cannot be a piece of land onto which isolated individuals put animals without talking to each other until it’s overused.

Hubert mentions Mastodon as an example for a digital commons – “Because everyone can always join in. … These are things that are quite clearly where you can say, yeah, this is digital and it is a commons. Because everyone can use it, everyone can take part. … You did not have to ask permission from anyone.”

Particularly this latter sentence is the signature formula of the Silicon Valley-adjacent hyper-individualised copyright lawyers behind Creative Commons. By using any combination of the CC license building blocks, an author signals to users that they are free to perform acts which by copyright law default are reserved to him. Once they see these signals on a work, users do not need to ask additional permission from the author or from CC or anyone else.

I will return to this, but first back to Hubert’s confusion. “But if you want to say, what is a digital commons, you have a far harder time. There are very academic definitions that do not quite help us.” Here I strongly disagree. Ostrom’s seminal 1990 book, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action is very worth reading and quite helpful for disentangling the issues at hand.

Hubert is seemingly unaware of Ostrom’s work, yet his intuition guides him to the insight that “we should also in many cases have governance like the Wikipedia has governance that people spend a lot of time on. OpenStreetMap has whole conferences to decide what to do.”

Public parks and streets are not commons either

Now we are no longer talking about the consumptive freedom of everybody allowed to use Wikipedia or OSM or a free-for-all pasture – ‘without having to ask permission’ – but about a collective who jointly creates and maintains a resource and spends a lot of time on making rules for itself for doing so sustainably.

The commons is not a ‘thing’. It is also not a label or a license attached to a thing that makes it a commons. Nor are public parks, streets and sidewalks commons, as US law scholars on both West and East Coast will regularly claim. This seems to be the result of the historic enclosure of the commons which led to them being dissolved into either private property, i.e. they disappeared, or – public property, in which case all that remained was a name.

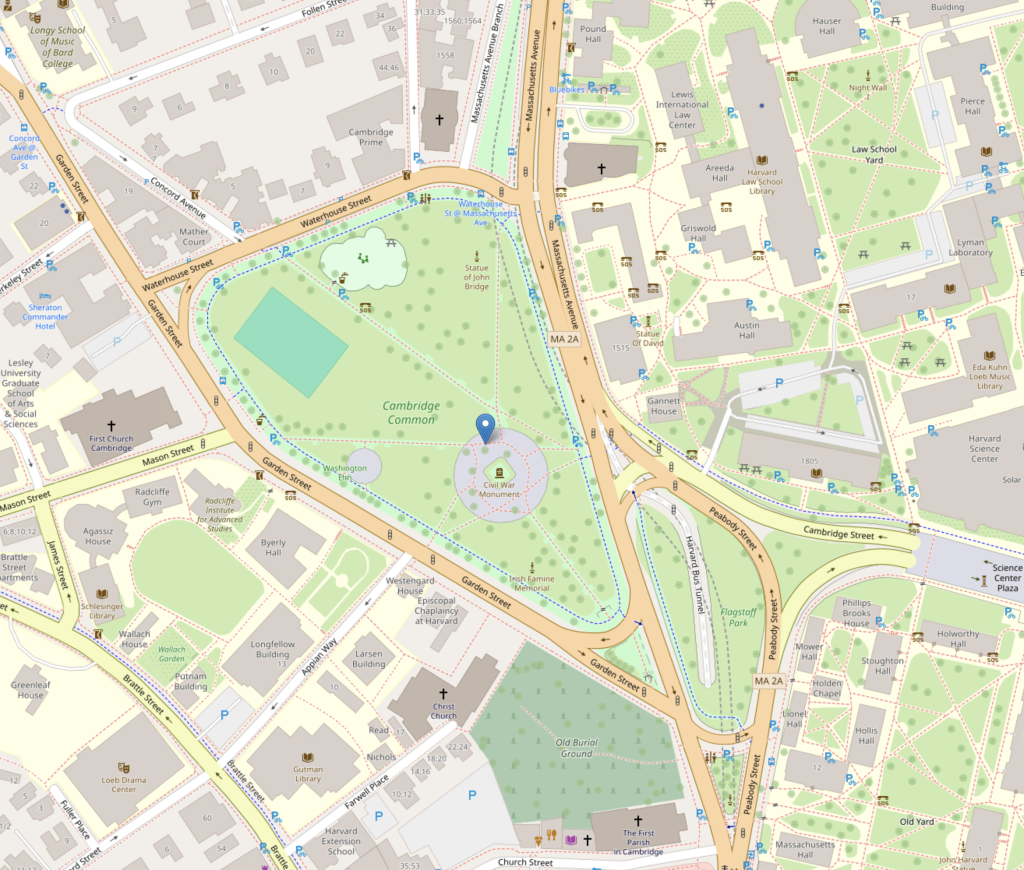

When you search for ‘commons’ on OSM in UK, US or Ireland, you will find parks, nature reserves, settlements, buildings that conserve the name ‘commons.’ Yet the name does not make them a commons.

These typically provide free access to all citizens who don’t have to ask permission. Not because they are a commons, but because they are owned and maintained by a national trust or by the state and run by the street and park authorities.

In contrast, a commons is a social formation, a community of commoners who sustainably make use of a joint resource. No community of commoners, no commons.

Hardin’s fallacy: Consumptive freedom without communication

The real tragedy is that even 26 years after Ostrom received the Nobel Prize in economics for refuting Hardin’s BS science, the word ‘commons’ still triggers if not the word, at least the idea of a tragedy. Even in good people like Hubert.

There is a video recording of Elinor Ostrom being amused about the naivety of Hardin’s approach: No data! Only an armchair thought experiment: Just imagine a pasture open to anyone. Where people didn’t talk to each other and just put on as many animals as they could! That became like a religion. The presumption is that people are helpless. They need either government to tell them what to do or to privatise the resource.

The idea that people could collectively self-organise did not even occur to Hardin. His tragedy of the commons consist in the fact that he does not talk about a commons at all, but about a free access regime.

Let’s remember that Hardin was a Malthusian ‘human ecologist’ preoccupied with the issue of overpopulation. He wasn’t concerned about people putting cows on meadows but about people putting more people into the world. And this respect he proclaimed: “Freedom to Breed Is Intolerable” (Hardin 1968).

In a natural setting, ‘parents who bred too exuberantly’ would have their offspring decimated by natural selection which would leave only the strongest to survive. Yet the welfare state grants security and healthcare to all.

“In a welfare state, how shall we deal with the family, the religion, the race, or the class (or indeed any distinguishable and cohesive group) that adopts over-breeding as a policy to secure its own aggrandizement? To couple the concept of freedom to breed with the belief that everyone born has an equal right to the commons is to lock the world into a tragic course of action.” (Hardin 1968)

What Hardin had in mind looks pretty much like what Trump is currently doing: dismantle the welfare state and let natural selection run its course. When the poor have been decimated or driven out of the country and immigrants are kept out, what remains is a WASP ethno-nationalist state of the rich. To top it off, Trump is even planning to celebrate his ‘achievements’ with Hunger Games (Forbes 19.12.2025).

The most widely cited sentence from Hardin’s infamous article is: “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.” Yet even he himself nearly thirty years later – in an interview that nobody knows – had to acknowledge that he was wrong. Or at least not careful enough. If he were doing it over again, he says, he would write: “In a crowded world, an unmanaged commons cannot possibly work.” He still cannot get the idea out of his mind that a commons is a free-for-all:

“I pointed out that if the world is not crowded, a commons may in fact be the best method of distribution. For example, when the pioneers spread out across the United States, the most efficient way was to treat all the game in the wild as a commons, an unmanaged commons (‘Just fire away’) because for a long time they couldn’t do any real damage.” (Hardin 1997)

By adding the attribute ‘unmanaged’ he did admit that he did not write about a commons at all because an unmanaged commons is an oxymoron. Again: a commons is not a thing that can be managed or unmanaged, instead it is precisely a form of collective management, of time-consuming communication. Hardin’s fallacy is to only perceive an individual’s consumptive use exercised without permission. Like in most cases of CC license use.

The real commons, revitalised by Ostrom

There is a long history of scholarship on actually existing commons and their enclosure. Who ever has read Karl Marx, Das Kapital, will remember that the ‘original accumulation’ of capital1 is based on two dynamics: the enclosure of the commons, leading to large masses of people forcefully torn from the land and thrown onto the labour market as ‘free’ proletarians, and colonisation of the Global South, the looting of its wealth and the enslavement of its people (Cf. Grassmuck 2013).

Max Weber in Economy and Society (1922) under the heading ‘Types of communitisation and socialisation’ describes the formation of a system as ‘closure to the outside’ through the original drawing of boundaries. This can be the members of a tribe or village jointly clearing forst or cultivating moorland areas, the association of fishing interests in a particular body of water, the closure of participation in the fields, pastures and other common land of a village to outsiders or an association of engineers that seeks to enforce a monopoly on certain positions for its members. These constitute a group-monopolisation of social and economic opportunities and thus the creation of ‘property’ in collective ownership. In a second step, according to Weber, the ‘closure to the inside’, a differentiation that he calls ‘appropriation’ of the monopolised shares by individuals, then creates private property.

It seems that Hardin’s tragic 1969 article essentially cut off that tradition of research by proclaiming – without data – that every commons inevitably leads to overuse. He gave the ‘commons’ a bad name.

To the point where Ostrom found it necessary to drop the word entirely and replace it with ‘common pool resources’ in order to save the idea. She spent most of her life’s work refuting Hardin’s article by conducting rigorous empirical studies on water management systems, fisheries, alpine high pastures, forestries and other natural resources in many countries that are managed as a commons and often have been for centuries. This is obviously only possible when 1) there is a clearly delineated community 2) who makes rules for themselves. These are unsurprisingly two of the eight design principles for sustainable commons into which Ostrom condensed the conclusions of her research into. I will return them in my own conclusions.

Ostrom, the only ever female economist to win a Nobel Prize, revitalised the idea that the commons is not only a tragic thing from the Middle Ages but a very present and practical but mostly overlooked social formation with much potential to help us find alternative solutions to many of today’s problems.

Her commons clearly resonate with contemporary research and have inspired fresh work on commons communities and practices.

Yochai Benkler has coined the concept of Commons-Based Peer-Production as a third way of resource management emerging in the digitally networked environment next to top-down managed firms and price-signal driven markets (Benkler 2002; 2016).

Philosopher Rahel Jaeggi analyses commons practices as counter-model to the alienation of capitalist wage labour by enabling communal production, participation and control, where individuals act in connection rather than isolation (Jaeggi 2018; Fraser & Jaeggi 2020).

Both Michel Bauwens (P2P Foundation) and Silke Helfrich have created large bodies of original work as well as libraries of resources on the commons.

Closer to home, i.e. the DC EDIC, Sophie Bloemen and David Hammerstein, in A Commons Approach to European Knowledge Policy (2015), recount the tragedy that “[f]or decades, the commons has been dismissed as a failed system”, a misconception steming from a Hardin’s infamous 1968 “essay.”

“While this understanding of the commons is widespread, a commons is, in truth, something richer and deeper. It is not just the resource alone, but a social system – one that arises through the interactions of people who devise their own locally appropriate, mutually agreeable rules for managing resources that matter to them. Value creation and stewardship in a commons occur through the active participation of a community of people. Or as the historian Peter Linebaugh has put it, ‘There is no commons without commoning.’” (ibid.)

The digital commons

Ostrom also ventured into grappling with information resources and digital objects. Those are not scarce in that they can be copied and shared endlessly without being diminished. If a GNU/Linux distro and Wikipedia can be used freely by millions without taking anything away from others – and without having to ask permission –, why should we have governance, as Hubert noted?

The GNU GPL grants maximum freedoms of use to software works but famously, in its copleft provision, requires reciprocity for productive use: if you create and publish a derivative work under this license you must do so under the same terms. Or as the preamble of the first verion reads: “To protect your rights, we need to make restrictions that forbid anyone to deny you these rights or to ask you to surrender the rights.”

A more general Definition of ‘Open’ also requires distribution of derivatives of the licensed work to be under the same terms of the original licensed work. Among the CC variants, only the Share-Alike building block achives the same effect.

So why this condition to reciprocate? The first answer: to prevent free-riding by making valuable modifications of the work of thousands of contributors and selling them as a closed proprietary product. This free-riding might frustrate the volunteers who maintain and develop Free Software and write Wikipedia articles. As I have argued elsewhere (Grassmuck 2011), the scarce resource that needs to be protected is the willingness to contribute.

It clearly points to something larger than an issue of individual users and individual producers. It implies a community of producers regulating their internal relations. And such a community, e.g. Wikimedians, can, of course, decide to change the terms of these relations, e.g. when Wikimedians voted to change the license from GNU FDL to CC-BY-SA in 2009.

What needs to be protected by the community of commoners is not the final product, but the community of producers itself. A commons needs governance, that people, as Hubert had remarked, spend a lot of time on.

The Digital Commons EDIC

And the DC EDIC will undoubtedly also spend a lot of time on it. A “European Digital Infrastructure Consortium“ (EDIC) is an EU instrument that enables Member States to jointly develop, establish and operate cross-border digital infrastructures with its own governance and legal personality.

Will the Consortium of states itself become infrastructure provider with a commons governance between them or will they rather facilitate the creation of an infrastructure commons by actors like the IT industry, academia and civil society? State actors, as Hubert noted, don’t typically build and operate digital infrastructure themselves, they prefer to procure it as a service. Funding programmes, calls and tenders are typical instruments of states to get the tech they want.

And from experience they know that dealing with hackers isn’t easy. Therefore a design feature for these kind of arrangements has proven itself: As a state, don’t talk to hackers directly, find friendly techies to do it for you.

An example is the Next Generation Internet EU funding programme, for which the European Commission commissioned the NLnet Foundation, which goes back to the guys who in the early 1980s originally brought the Internet to Europe, to handle the selection and management of projects.

Similarly, applicants to the German Prototype Fund are met by an organisation set up by the Open Knowledge Foundation Germany who have created something that is not intended by the normal funding activities of the German Ministry for Research: low-threshold support for individual developers or small groups allowing them to work on a software prototype for six months. The Prototype Fund has simplified the application procedures to the max and guides applicants through it. An additional interface between Ministry and hackers is the German Aerospace Center (DLR) that acts as project management agency. Therefore the EDIC is well-advised to set up a similar interface towards the hackers who it enables to develop cool stuff on different layers of the Internet stack.

Whatever the EDIC builds, it needs to adhere to Hubert’s six requirements for a successful digital commons. It needs to be Free Software and open standards, apply state of the art usability and advertise its goodies.

It also needs to go back to Ostrom’s eight design principles for collective self-governance: 1) Clearly defined boundaries delineate who is in and who is out of the obligation to support the common resource, while extracting units of the digital good remains free for all. 2) The congruence between appropriation and provision rules and local conditions points to the limited ability of commoners to contribute to developing and maintaining the common digital resource, including moderation of social networks. Upholding this congruence requires a commons of care: the community at large needs to ensure the wellbeing of those who create the basis of their joint online environment, e.g. the fediverse, and prevent burn-out. 3) Collective-choice arrangements refer to the internal democracy of the commons, allowing individuals affected by the operational rules to participate in modifying these rules. 4) The conditions of the commons need to be monitored, 5) there need to be graduated sanctions against those who violate the agreed rules and 6) conflict-resolution mechanisms to settle disputes. 7) The recognition of rights to organise by external governmental authorities is ensured, as the commoners in this case are governments. And finally, as a European consortium, 8) all the above mechanisms need to be organised in multiple layers of nested and federated enterprises, i.e. the European layer has to have corresponding structures on the national and local level.

Never before has the commons been addressed at such a high level of policy making. Let’s hope the EDIC will be guided by the right vision of a commons and spill over into inspiring forms of commoning in other areas as well.

Notes

1‘Ursprüngliche Akkumulation’, unfortunately regularly mistranslated to ‘primitive accumulation.’